Boeotia, Epaminondas, Stater

ca. 364-362 BC - Thebes - Silver - NGC - Ch AU 4/5 4/5

PLEASE NOTE: this collector's item is unique. We therefore cannot guarantee its availability over time and recommend that you do not delay too long in completing your purchase if you are interested.

Boeotian shield.

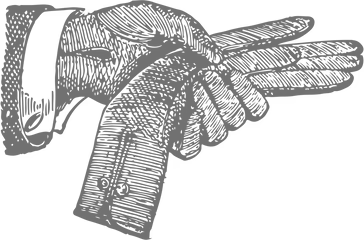

Amphora with rosette above, all within concave circle.

Graded NGC Ancients Ch AU Strike: 4/5 Surface: 4/5 Flan flaws. Beautiful specimen, having been cleaned but beautifully repatinated with powerful golden tones, particularly around the Beotian shield! The 5 letters of the magistrate's name are clearly visible, which is rare. Unfortunately, we must point out two flan breaks, one on the shield and another on the reverse to the right of the amphora. The flan is quite thick, but very cracked slightly when struck at 3h. Note that the reverse die has been re-engraved and originally indicated the magistrate's name EΠ-ΠA, the letters ΠA are still clearly legible under AM. The reuse of the reverse die is also evident from the numerous small breaks in the rose petals, as well as in the amphora's handles. Recent studies suggest that this coinage is attributable to the famous Theban general and statesman Epaminondas, who died at the Battle of Mantinea in 362 BC, where the Thebans and Spartans fought for hegemony over Central Greece. The man is remembered for the crucial role he played in the rise of Thebes as a major Greek city in the first half of the 4th century BC. However, his death led to the decline of the city, without this skilful politician and without his successors who died on the same day. Thebes made peace with its enemies, unable to exploit its victory, thus paving the way for Philip II of Macedonia to conquer the regions and cities then allied with Thebes, starting with Thessaly around 352 BC, towards complete domination in 338 BC with the battle of Chaeronea. Hepworth, Epaminondas pl. 3, 3 (same rev. die); Hepworth 32 (same rev. die); BCD Boiotia 543 (same dies); HGC 4, 1333; Traité III 267, pl. CCI, 16 (same rev. die). From the Pythagoras Collection. Ex CNG Triton XIII, 5 January 2010, lot 1201.

EΠ-AMI

12.26 gr

Silver

Silver can fall into your pocket but also falls between copper and gold in group 11 of the periodic table. Three metals frequently used to mint coins. There are two good reasons for using silver: it is a precious metal and oxidizes little upon contact with air. Two advantages not to be taken for granted.

Here is thus a metal that won’t vanish into thin air.

It’s chemical symbol Ag is derived from the Latin word for silver (argentum), compare Ancient Greek ἄργυρος (árgyros). Silver has a white, shiny appearance and, to add a little bit of esotericism or polytheism to the mix, is traditionally dedicated to the Moon or the goddess Artemis (Diana to the Romans).

As a precious metal, just like gold, silver is used to mint coins with an intrinsic value, meaning their value is constituted by the material of which they are made. It should be noted that small quantities of other metals are frequently added to silver to make it harder, as it is naturally very malleable (you can’t have everything) and thus wears away rapidly.

The first silver coins probably date back to the end of the 7th century BC and were struck on the Greek island of Aegina. These little beauties can be recognized by the turtle featured on the reverse.

The patina of silver ranges from gray to black.

The millesimal fineness (or alloy) of a coin indicates the exact proportion (in parts per thousand) of silver included in the composition. We thus speak, for example, of 999‰ silver or 999 parts of silver per 1 part of other metals. This measure is important for investment coins such as bullion. In France, it was expressed in carats until 1995.