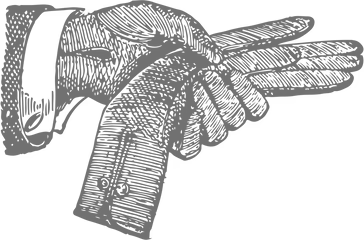

Magnentius, Solidus, 350-351

Arles - Very rare - Gold - MS(60-62) - RIC:132

Sold

Bust of Magnentius, bareheaded, draped, cuirassed, right.

Victory, winged, draped, standing right, holding palm over left shoulder, and Libertas, draped, standing left, holding transverse sceptre in left hand; between them, the support a plain shaft carrying a trophy

Splendid specimen of a Solidus of Magnentius, emperor with a very short reign (350-353). This coin, struck in Arles, in the south of France, depicts the allegories of Victory and Liberty, thus highlighting the emperor's position as liberator of the Roman people, an element also emphasised by the legend. The association of Magnentius's portrait with the observe legend is also extremely rare for coins from this period: beginning with "IM" and the emperor's name here, it stands in complete contrast to the other captions, which almost always begin with "D N" followed by the emperor's name at this period. This reminds the Roman coins of earlier periods beginning exclusively with "IMP", to be translated as "Imperator". This is a highly exceptional case for an extremely well-preserved specimen, which still shows some traces of the mint lustre around the reliefs. Several die breaks can be seen in the letters of the captions, in the fields on the obverse and on the reverse, and on the portrait, showing that this coin was struck with very worn dies.

IM CAE MAGN-ENTIVS AVG

VICTORIA AVG LIB ROMANOR // PAR

4.34 gr

Gold

Although nowadays gold enjoys a reputation as the king of precious metals, that was not always the case. For example, in Ancient Greece, Corinthian bronze was widely considered to be superior. However, over the course of time, it has established itself as the prince of money, even though it frequently vies with silver for the top spot as the standard.

Nevertheless, there are other metals which appear to be even more precious than this duo, take for example rhodium and platinum. That is certain. Yet, if the ore is not as available, how can money be produced in sufficient quantities? It is therefore a matter of striking a subtle balance between rarity and availability.

But it gets better: gold is not only virtually unreactive, whatever the storage conditions (and trouser pockets are hardly the most precious of storage cases), but also malleable (coins and engravers appreciate that).

It thus represents the ideal mix for striking coins without delay – and we were not going to let it slip away!

The chemical symbol for gold is Au, which derives from its Latin name aurum. Its origins are probably extraterrestrial, effectively stardust released following a violent collision between two neutron stars. Not merely precious, but equally poetic…

The first gold coins were minted by the kings of Lydia, probably between the 8th and 6th century BC. Whereas nowadays the only gold coins minted are investment coins (bullion coins) or part of limited-edition series aimed at collectors, that was not always the case. And gold circulated extensively from hand to hand and from era to era, from the ancient gold deposits of the River Pactolus to the early years of the 20th century.

As a precious metal, in the same way as silver, gold is used for minting coins with intrinsic value, which is to say the value of which is constituted by the metal from which they are made. Even so, nowadays, the value to the collector frequently far exceeds that of the metal itself...

It should be noted that gold, which is naturally very malleable, is frequently supplemented with small amounts of other metals to render it harder.

The millesimal fineness (or alloy) of a coin indicates the exact proportion (in parts per thousand) of gold included in the composition. We thus speak, for example, of 999‰ gold or 999 parts of gold per 1 part of other metals. This measure is important for investment coins such as bullion. In France, it was expressed in carats until 1995.