Sicily, Dionysios I, Decadrachm

ca. 405-390 BC - Syracuse - Unsigned work

Sold

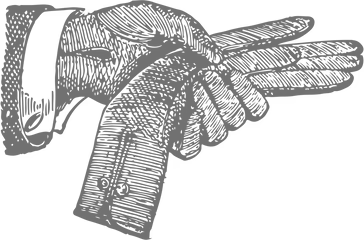

Charioteer holding kentron in extended right hand and reins in left, driving galloping quadriga left; above, Nike flying right, crowning charioteer with wreath held in her extended hands; below exergual line, military harness, shield, greaves, cuirass, and crested Attic helmet, all connected by a horizontal spear; [AΘΛA below].

Head of Arethusa left, wearing wreath of grain ears, triple-pendant earring, and pearl necklace; ΣY-P-A-K-OΣIΩN above between locks, pellet below chin, scallop shell behind neck, four dolphins swimming clockwise around.

Unsigned work with dies in the style of Euainetos. Struck circa 405-390 BC, under the reign of Dionysius I, known as Dionysius the Elder (405-367 BC), tyrant of Syracuse. Masterpieces of ancient Greek numismatics, decadrachms were among the most prized and highly appreciated coins of Ancient Greece. Their aspect, with their very wide flans and heavy weight, as well as their exceptional engravings, were elevated to the rank of works of art, to the point that their authors signed their creations. The most famous of these were the Syracusan engravers Kimon and Euainetos, who officiated under the reign of Dionysius the Elder, as well as their disciples and successors, who were able to assimilate, master and reproduce their style with great virtuosity. It is the Euainetos style that was used for the engraving of this coin, recognisable by the wreath of grain ears and the hair left free, without a net to hold it. The subtlety of the portrait in contrast to the vivacity of the quadriga is remarkable. The features of the portrait of Arethusa inspire calm and serenity, with a few strands of hair standing out from the hairstyle as if floating gently in the wind. Meanwhile, the quadriga evokes ardour, with almost none of the horses' hooves touching the ground, reinforcing the sensation of impetuosity in the carriage. This detail gives a realistic sense of movement, as do the non-parallel heads of the horses, giving the impression that the engraver has captured a moment of their agitation as they are galloping. These engravers may have worked from 405 BC, or perhaps 400 BC, and their style continued to be used by them or their pupils until the end of the tyrant's reign. This coincided with the political changes that Dionysius wanted to bring to Syracuse as soon as he assumed power, where he concluded a peace treaty with Carthage and was voted the city's full authority as sole strategos, having his colleagues deposed. This allowed him to greatly strengthen the city's defences, and his poliorcetes (strategists specialised in sieges) were put to work developing or improving powerful throwing weapons for this purpose. He also strengthened the army and fortifications of the city, erecting a 27km wall all around it. The importance of these projects generated considerable costs, and it is possible that the minting of decadrachms was launched in order to finance them. In fact these coins represented a considerable amount of money and helped to provide large payments to cover the substantial costs of these large-scale projects. The types could evoke the total victory of the Syracusans in 413 BC, allies of Sparta, against the Athenian military expedition to Sicily that had begun two years earlier. The word ‘AΘΛA’ (Athla) should be found on these coins under the military trophies in the exergue, even though it is off-center. This refers to the lexicon of fighting and combat, so it echoes the destruction of the Athenian forces and the capture of their weapons to make trophies, a tradition in this period of displaying the weapons of the defeated after victories. The weapons, presumably Athenian, are represented by the Attic helmet and the large round shield (the hoplon) of the hoplites, elite soldiers heavily armed and organised in phalanxes, the main force of Greek armies, whose spear, one of this soldier's main weapons, is also represented. While the contemporaries of these issues had no difficulty in understanding the iconography of these superb coins, it is more difficult today to comprehend the implicit meaning of these representations. But by tracing the events affecting the city and looking at the types of coinage that follows, it is still possible to interpret them and appreciate the beauty of the engraving and their meaning. This coin has a well struck and very thick flan, an orientation at 5 o'clock. The portrait of Arethusa on the reverse is complete, with a die break behind the head and a slight double-strike. The ethnic letters can be seen between her hair, but the flan is still quite narrow, with only one dolphin completely visible, and only the back of a second one directly below the neck, all the others being off-center. On the observe, the shield to the far left of the exergue is also off-center. However, the engravings of the quadriga and the Nike are very well centered. As the side most regularly showing die breaks on known examples, there is a rough appearance in the field as well as a break on the wing of Nike, indicating the beginning of the die wear. For the side with Arethusa, we have here one of the rarest reverse die (F.IXa). This variety with the dot under the chin and the scallop shell was known in six examples when A. Gallatin wrote his book in 1930. Among the three obverse dies associated with it and identified by the author, we have on this decadrachm the obverse die R.XXI. Only three examples have been listed for this combination, each in a public collection, at the Münzkabinett in Berlin, in Palermo and in Napoli (5117). We should also note the example from the Delepierre collection, which he seemed to be unaware of, with the same reverse but a observe die association he didn't record. We therefore have here a coin of great rarity. The scallop decadrachms are a fairly small group when we look at the population found by Gallatin, limited in time, making these examples of decadrachms quite rare today, and much sought after by collectors. They are all the more so, on one hand for their appearance, shape and size, which make them outstanding coins, and on the other for the symbolism of the engravings, and sometimes for their rare varieties. Gallatin, dies R.XXI/F.IXa; R. Scavino 56 (D18/R26a); HGC 2, 1299; BMC Sicily 179-180 (same obv.); Naville XII, 955-956 (same obv.); Virzi Collection (J. Hirsch XXXII, 14 November 1912), 327 (same rev.); Delepierre 685 (same rev.); SNG Blackburn 187 (same rev.); SNG ANS 374 (same rev.); Rizzo Pl. LIV, 2 - 3 (without dot); Pozzi 1274 (Coll.) & 617 (Sale) (without dot). Ex Schweizerische Bankverein (Swiss Bank), Auktion 17, Basel, Switzerland, 27 January 1987, lot 15 & ex Sabine Bourget Auction, 20 March 1994, lot 11. Faune d'Argent Collection.

ΣYPAKOΣIΩN

43.29 gr

Silver

Silver can fall into your pocket but also falls between copper and gold in group 11 of the periodic table. Three metals frequently used to mint coins. There are two good reasons for using silver: it is a precious metal and oxidizes little upon contact with air. Two advantages not to be taken for granted.

Here is thus a metal that won’t vanish into thin air.

It’s chemical symbol Ag is derived from the Latin word for silver (argentum), compare Ancient Greek ἄργυρος (árgyros). Silver has a white, shiny appearance and, to add a little bit of esotericism or polytheism to the mix, is traditionally dedicated to the Moon or the goddess Artemis (Diana to the Romans).

As a precious metal, just like gold, silver is used to mint coins with an intrinsic value, meaning their value is constituted by the material of which they are made. It should be noted that small quantities of other metals are frequently added to silver to make it harder, as it is naturally very malleable (you can’t have everything) and thus wears away rapidly.

The first silver coins probably date back to the end of the 7th century BC and were struck on the Greek island of Aegina. These little beauties can be recognized by the turtle featured on the reverse.

The patina of silver ranges from gray to black.

The millesimal fineness (or alloy) of a coin indicates the exact proportion (in parts per thousand) of silver included in the composition. We thus speak, for example, of 999‰ silver or 999 parts of silver per 1 part of other metals. This measure is important for investment coins such as bullion. In France, it was expressed in carats until 1995.

An “AU(50-53)” quality

As in numismatics, it is important that the state of conservation of an item be carefully evaluated before it is offered to a discerning collector with a keen eye.

This initially obscure acronym comprising two words describing the state of conservation is explained clearly here:

About Uncirculated(50-53)

This means – more prosaically – that the coin has circulated well from hand to hand and pocket to pocket but the impact on its wear remains limited: the coins displays sharp detailing and little sign of being circulated. The number (50-53) indicates that at least half of the original luster remains. Closer examination with the naked eye reveals minor scratches or nicks.

You might be wondering why there are different ranges of numbers behind the same abbreviation. Well, we’ll explain:

The numbers are subdivisions within a category, showing that the state of conversation is the same but coins may be at the higher or lower end of the scale. In the case of AU, the range (55-58) indicates that the luster is better preserved in than a similar coin described as (50-53).